|

MedievalEuropeOnline

the web home of Medieval Europe: A

Short History

|

Primary Sources: The First Valentine

Here's an example of the basic building block of history--a primary source (or first-hand account) from the past.

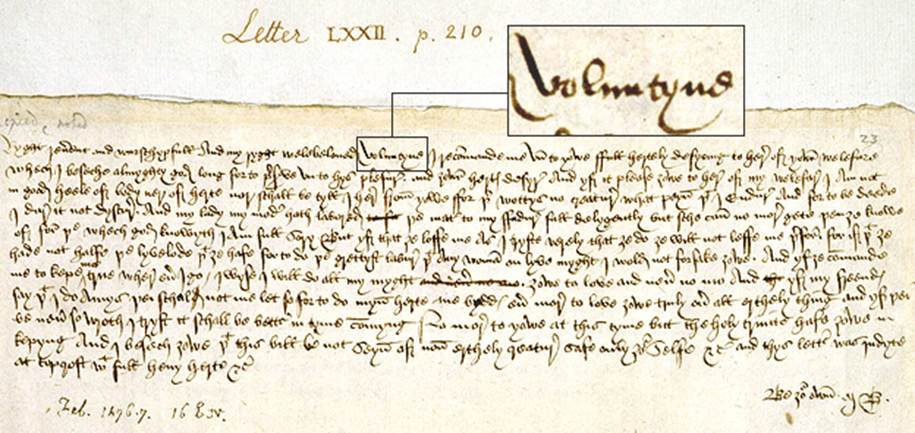

This is a letter written in February 1477. The author was a young, well-born woman named Margery Brews, and she sent the letter to a young gentleman named John Paston. She and John were courting, and their parents were negotiating what each would contribute to help the young couple marry. It was not at all clear that the two families would reach an agreement.

This letter is the first reference in English to the celebration of the feast day of St. Valentine as a romantic day for lovers.

In this letter, Margery both expresses love for John and does some negotiating herself. Here's the original letter:

Here's a modern translation of the text by Diane Watt:

Most respected and honourable and my most dearly-deloved Valentine, I commend myself to you with all my heart, desiring to hear of your happiness, which I pray Almighty God to preserve according to His will and your heart's desire. And if it pleases you to hear how I am, I am not in good health in body nor in heart, nor will be until I hear from you. For no one knows what pain it is I suffer and even on pain of death I dare not disclose it.

And my lady my mother has pursued the matter [that is, the matter of their marriage settlement] with my father very industriously, but she cannot get any more than you know of, because of which, God knows, I am very sorry.

But if you love me, as I truly believe you do, you will not leave me because of that. Because even if you did not have half the wealth that you do, and I had to undertake the greatest toil that any woman alive should, I would not forsake you. And if you command me to remain faithful wherever I go, I will indeed do everything in my power to love you and no one else ever. Even if my friends say I am acting wrongly, they will not prevent me from so doing. My heart commands me to love you truly above all earthly things for evermore. And however angry they may be, I trust it shall be better in time to come.

No more to you for now, but may the Holy Trinity protect you. And I beg you that you will not let anyone on earth see this letter, except yourself. And this letter was composed at Topcroft with a very heavy heart, etc.

By your own, MB

Nice, eh? Margery Brews tell John Paston that she loves him, but she also tells him that he and his parents are not going to be able to squeeze another penny from her family.

Here's an interesting tidbit. Despite Margery Brews' request that John Paston "not let anyone on earth see this letter," it was well-known to a third person: Thomas Kela, the Paston clerk who wrote it out. Gentlewomen and gentlemen often used scribes, even when they could write themselves. We think Margery Brews signed the letter herself (see the MB in the lower right corner?), but all the rest is in the handwriting of Thomas Kela.

The story has a happy ending: Margery and John did marry, and their marriage was a happy one.

FROM ORIGINAL LETTER TO PRINTED TRANSLATION

It takes several steps to get from the original latter to a translation.

Here's the original letter again:

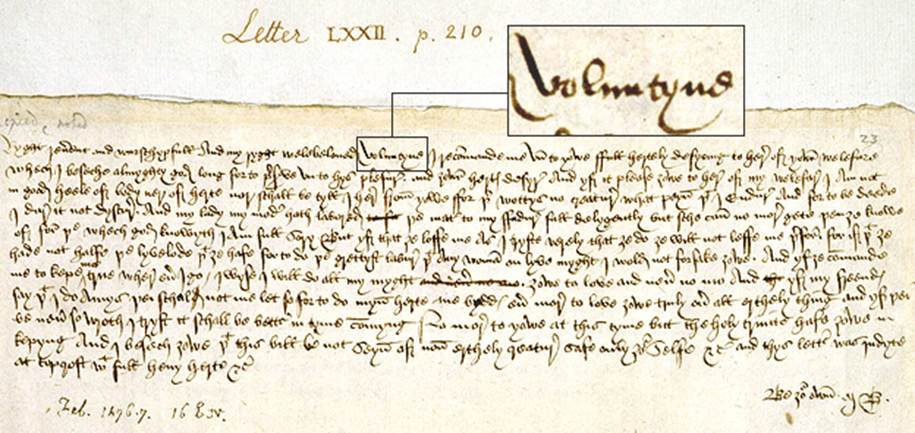

STEP 1: TRANSCRIPTION. In transcribing, a historian simply writes out the original text, letter by letter. I'll transcribe the first two lines for you.

LINE 1: Ryght reverent and wurschypfull and my ryght welebeloved

Voluntyne I recommande me unto yowe, ffull hertely desyring to here

of yowr welefare

LINE 2: whech I beseche Almyghty God long for to preserve un to

hys plesur and yowr herts desire . . .

This step is challenging, and to prepare for it, many medievalists spend years studying paleography--that is, old handwriting. You can probably make out some of the words yourself--like "Voluntyne" and also perhaps "welebeloved." But many of the letters and abbreviations are obscure, and historians have to master them. Here's a link to an online guide to the study of old documents and handwriting:

STEP 2: MODERNIZATION. This involves updating of spelling and punctuation. Here goes:

Right reverend and worshipful and my right well-beloved Valentine, I recommend me unto you, full heartily desiring to hear of your welfare, which I beseech Almighty God to preserve unto his pleasure and your heart’s desire.

This step can be tricky, especially because a misplaced comma or period can sometimes change the sense of a passage. Not here, but sometimes.

STEP 3: TRANSLATION. Even though we can understand it, Middle English is a different language from the English of today. Here's DIane Watt's translation of these two lines:

Most respected and honourable and my most dearly-beloved Valentine, I commend myself to you with all my heart, desiring to hear of your happiness, which I pray Almighty God to preserve according to His will and your heart’s desire.

This sounds better to our modern ears, doesn't it? But do you agree with all the changes? Is "respected" a good replacement for "reverend"? "Honourable" for "worshipful"? God's "will" for his "pleasure"? Translaters have to make lots of tough judgment calls.test podcast

SOURCES: The transcription and modernization are my own. For the image of the original letter, see BBC report at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-12419712. For the modernized text, see Diane Watt, ed., The Paston Women: Selected Letters (2004), pp. 127-8.